The future's here, and you can hold it in your hand

Everyone knows cinema’s a tough gig to get into. A budding novelist can sit in a cafe with a cheap notebook and a dream; the next Banksy only needs a wall and a can. But a movie maker needs a crew, and an editor, a colorist, a script, and an equipment list that goes on forever.

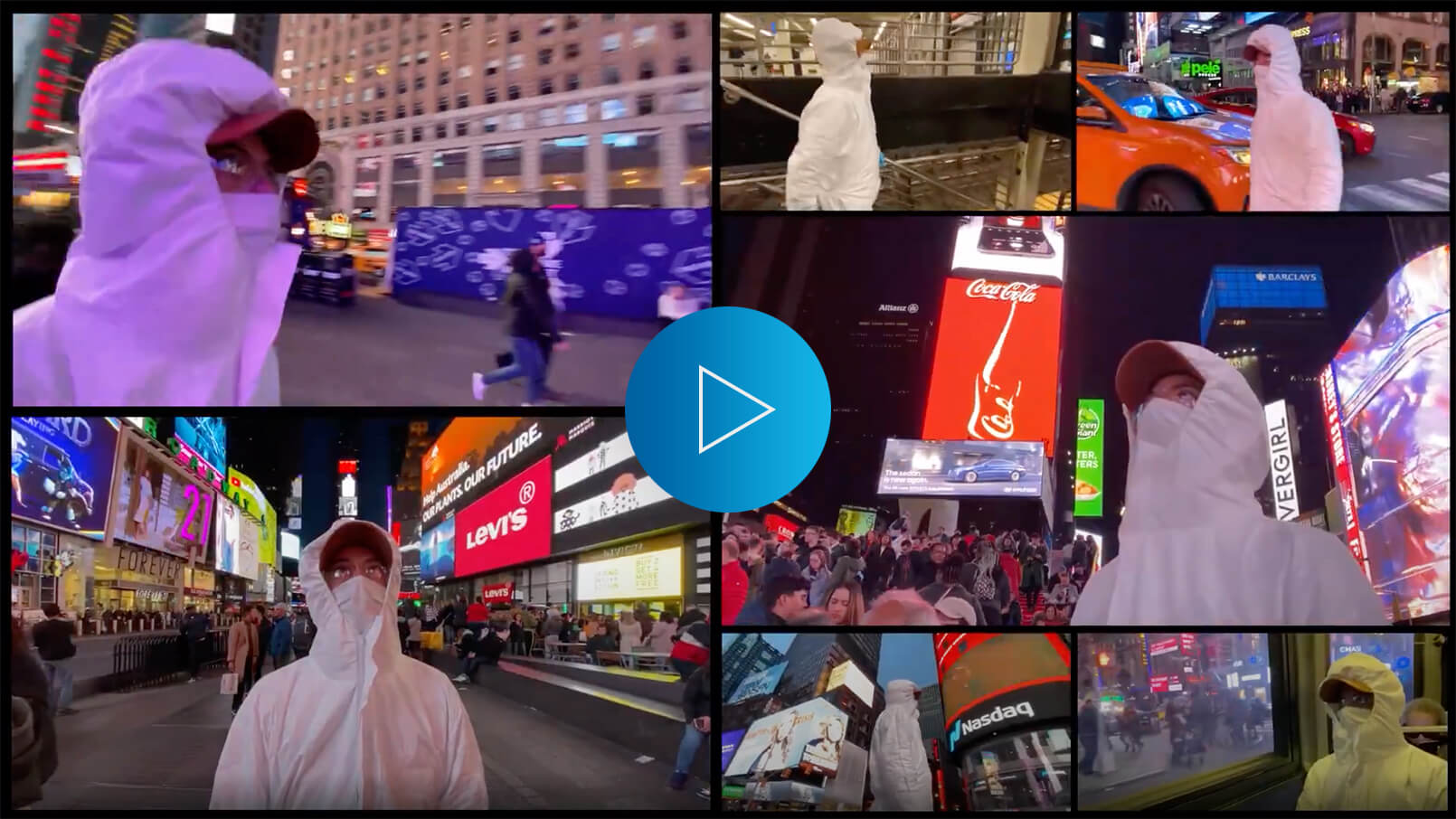

So it’s easy to dismiss smartphone movies as a novelty and as inconsequential TikTok nothings that will soon be forgotten. But that viewpoint ignores that their real potential isn’t the finished product, but the power to experiment they put in people’s hands. Their story may start with image capture on a small screen, can it end with image delivery on a large one? Smartphone film festivals think so.

SmartFone Flick Fest

Angela Blake is a co-founder and director of SF3 (SmartFone FlickFest), a hugely successful international festival held in Sydney, Australia. Though it’s now in its eighth year, even Angela says that right from the beginning, “we were adamant that we knew smartphones were never going to replace traditional cameras.” And she speaks from personal experience. Both she and her fellow founders have strong arts rather than tech backgrounds; Angela herself is a graduate of The New York Film Academy’s Acting for Screen Program and has a feature film called Burnu in the works.

No, what intrigued Angela was the democratization this new technology would bring. While smartphone technology doesn’t magically let you make feature movies—you still need talent and a heap of other stuff for that—what it does is empower everyday people to easily tell and publish stories using moving images – and that has never happened at scale before.

“Smartphone filmmaking is accessible. It really cuts down barriers, and because it’s a bit of an underground movement, there are huge communities. I think we all feel excited and lucky to be doing something new, with new rules, and bringing it to the mainstream. There’s a really fun kind of feel when you’re in this space.” She provides that missing link between small screen and large, sharing content with live audiences where it can be properly appreciated.

Claiming its moment

Mainstream cinema has noticed. American film director Steven Soderbergh says smartphones are now one of the cameras in his arsenal, and Angela says she sees “emerging or professional filmmakers who are between gigs or can’t get funding turning to smartphones as an accessible and affordable tool. I really think this technology is claiming its moment now.”

Pressure’s building from below too. The generation that has grown up with smartphones and immersed in YouTube is visually literate. Even if they’re not making movies themselves, their understanding of filmmaking grammar far exceeds their parents’. SF3 runs workshops, and Angela says, “Adults are still quite freaked out when it comes to editing—really overthinking things like frame rate and aspect ratios—but the kids aren’t thinking about any of this stuff. Before I’m finished speaking, they’re up and shooting, and they’ve already edited their film during their lunch break. They’ve got this inside them—and the adults don’t.”

Making feature films still demands feature film resources, and nobody at SF3 believes that’s changing. The real change is in the visual literacy of the makers and the watchers: they and their tiny smartphone screens are about to drive cinema’s next new wave, and it’s going to be a big one.